How to Protect Shelter Animals from Killing and Shelter Workers from Exposure

Every day now, I am receiving an alert of another shelter or pound closing to the public for adoptions. Many of these are pounds with a history of routinely putting animals to death. Others are private humane societies, but this means they are not pulling animals from pounds in their communities where the animals are now under a heightened death threat.

How should shelters respond to this time of crisis? By doing everything in their power to limit intakes and maximize live placements. Not only would doing so protect the lives of animals, but by reducing the number of animals entering the shelter and increasing the number fostered and adopted and thus in need of care, it would reduce the need for staff as well.

Despite mandatory lockdowns in many jurisdictions, “essential” services remain open. This has been interpreted to mean restaurants with “to go” service, Starbucks (for mobile orders), hardware stores, and others. It should go without saying that an animal shelter is one, too. But tragically, that’s not how shelters are classified when they close to adopters. NJ Animal Observer, for example, reports a pound in a New Jersey community which has ceased doing adoptions, even though liquor stores and golf courses are allowed to remain open.

While limiting access and employing common-sense precautions to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus make sense, ceasing adoptions does not. It puts the lives of the animals at risk, even though they are not a risk factor for transmission. Indeed, beyond risk, it is a death sentence.

Adoptions in the Age of Pandemic

Despite being closed to the public and to volunteers, staff are still required to come in and run daily operations, even if in a reduced capacity. They are still intaking animals as an “essential” service and caring for them during mandated holding periods. Given that they are there, they should also be focusing on adoptions and foster home recruitment, both of which would eliminate killing.

Media coverage relating to the coronavirus is non-stop, and the media is anxious for new angles by which to cover it. Now is the time for shelters to appeal to the best instincts of humanity and to enlist their community in shared service. They should explain what it means when animals come in, but are not made available for foster or adoption. They should explain that staff are required to care for the animals, and helping animals means helping people, too: the more animals who are adopted or placed in foster homes, the fewer “essential” staff is required.

To reduce intakes, shelters should be asking people considering surrendering to please wait on doing so, if they can, until this crisis is over. They should ask people who find stray animals to house them at their home if they can. They should humanely divert intakes where appropriate by, for example, expanding return to field for healthy stray cats.

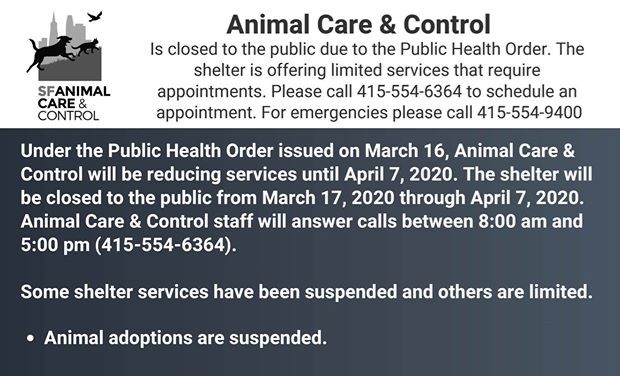

As for adoptions and given 21st century technology, there are many ways shelters can continue to adopt out animals or place them in foster care despite shut downs or reduced visitation. In addition to an appointment system, as LifeLine Animal Project is doing, over 20 years ago when I ran daily operations at the San Francisco SPCA, we had a program called “Dial a Cat” where residents with transportation challenges, such as the elderly, the infirm, and those with other mobility issues, could call in and adopt over the telephone and we would deliver the cat to the home. Today, doing so is even easier.

A shelter can do online adoptions, as well as video and live-stream meet-and-greets, as the SPCA of Wake County is doing (but only in part, a missed opportunity). They can also do foster-to-adopt, do trial runs, and so much more. With creativity, ingenuity, and technology, animals on death row could be given opportunities for loving homes, without putting people at heightened risk.

When a call was put out to the community for emergency foster homes in Kern County, CA, this week, the response was overwhelming. To significantly reduce human contact, the process was initiated as a drive-thru. “By the end of Wednesday, 88 pets had been put in temporary homes.” Adoptions can be similarly done.

Expanding the Safety Net

We live in a society in which most people want to maximize the happiness of cats and dogs. It is the job of animal shelters to educate them about how they can do so while providing opportunities for them to act. With schools closed, people off of work or working from home, and seeing their communities in need and wanting to help in ways big and small, shelters do not have to, and should not, close for adoption.

The recipe for saving lives remains the same as before the coronavirus pandemic, albeit with the need for greater urgency and more creativity:

- Do good things for animals.

- Tell people about it.

- Ask for their help.

Although I am gratified that many of the shelters which are closing are making an effort to get their animals into foster homes and others are humanely diverting intakes, an animal shelter is an “essential” activity not just for intakes, but for adoption. In fact, it is essential in every meaning of the word “shelter” and every aspect of their operations. Our fellow (non-human) Americans are completely reliant on us to ensure their welfare and by eliminating adoptions, we are not living up to our responsibilities. We owe them the protection that is their right as dependents in our social contract and as residents of our mixed human-animal community.

While the novel coronavirus pandemic not only exposed deep insufficiencies in our country’s social and public health safety net for people, it also exposed, in some quarters, our total abdication of the safety net we owe dogs, cats, rabbits and other animals. As philosopher David Pearce writes, “Over the last century, a welfare state for humans was introduced in Western European societies so that the most vulnerable members of our own species wouldn’t suffer avoidable hardship.” “The problem,” as he notes, “is not just that existing welfare provision is inadequate: it’s also arbitrarily species-specific. In common with the plight of vulnerable humans before its introduction, the welfare of vulnerable non-human animals depends mostly on private charity. No universal guarantees of non-human well-being exist.” Ideally, animal shelters would provide those guarantees, through embrace of the No Kill philosophy and the programs and services which make it possible — programs that can save lives not only during ordinary circumstances, but extraordinary situations like the one we are currently facing. By closing their doors completely, they are failing to live up to the debt and duty we owe. This shared crisis should not be an automatic death sentence for animals.

And though I am mindful of our obligation to “flatten the curve” by social distancing and quarantining in place (where possible), as a society we have other obligations as well — obligations that cannot be put on hold and that can be initiated in a way that reduces risks for shelter workers, too.

Shelters that are experimenting with creative ways to remain true to their mission at this time of crisis are encouraged to contact the No Kill Advocacy Center so we can share your approach with others.

————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.