This essay first appeared in Irreconcilable Differences: The Battle for the Heart & Soul of America’s Animal Shelters. To learn more and/or purchase a copy, click here.

I’ve devoted the last [20] years of my life to reforming animal shelters in the United States (far longer doing rescue). I’ve worked at two shelters that have the highest rates of lifesaving in the nation: one as its Director of Operations and the other as the Executive Director. I’ve also worked and consulted with dozens of shelters nationwide. Currently, I run the national No Kill Advocacy Center, which is dedicated to ending the systematic killing of animals in shelters.

In my work to reform antiquated shelter practices, I often face traditional sheltering dogma that is a roadblock to lifesaving innovation. Too many shelters operate under false assumptions that cause animals to be killed. If shelter directors reevaluated, rather than hid behind conventional wisdom, they would more be more successful at saving lives.

One of the most enduring of these traditional dogmas is that animal shelters must kill because the public cannot be trusted with animals. I faced this attitude when I arrived as the new executive director of the Tompkins County SPCA in upstate New York. Other than prohibiting killing, I had planned to quietly observe the agency for the first couple of days on the job: I wanted a sense of how the agency was run. An elderly gentleman and his wife came in as I was standing behind the counter observing our adoption process. After looking at the animals for some time, they came to the front counter to adopt a cat. The man told the adoption counselor how he adopted a cat from us 15 years ago. “She died one year ago today,” he said. As much as they missed having a cat, he explained, he and his wife waited one year to get a new cat because they wanted to mourn her appropriately. As he told the story, he began to cry and walked away. His wife explained that her husband loved their cat very much, but they were indeed ready to love another one. Because they found a great cat here 15 years ago, they came back to us.

They filled out the application: Do they consider the adoption a lifetime commitment? Yes. Do they have a veterinarian? Yes. What happened to their other cat? Died of cancer. “In my arms,” the old man said. But one thing caught the adoption counselor’s eye. When they came to the question asking about where the cat would live, they had checked the box: “Mostly indoors, some outdoors.”

“Sorry,” the adoption counselor said. “We have a strict indoor-only rule.” She denied the adoption. They were stunned. I was stunned.

What happened to “15 years,” “in my arms,” “wanted to mourn her appropriately,” “lifetime commitment”? I overruled the counselor and gave them the cat. No fees, no more paperwork: “Let’s go get your kitty,” I said. I put her in their carrier and told them we’d see them in another 15 years. They thanked me and left.

I looked at the adoption counselor and told her: “We’ve got to take a more thoughtful approach to adoptions.”

She stared at me blankly.

“Ok,” I said, “Let me put it this way. Outdoor cats may face risks, but it largely depends on circumstances. We need to use common sense. This isn’t downtown Manhattan. This is a rural community. I only saw one car on my way to work this morning. In fact, given how safe it is, people should be required to let the cat go outside.” I smiled.

Nothing.

So I continued: “Outdoor cats may face risks, but so do indoor cats. They are just different ones and we don’t always see the causal connections, such as obesity and boredom. Fat and bored cats are at risk for diabetes, heart problems, and even behavior problems.” Still nothing. My then shelter manager stepped in and said that they were following the policies of the Humane Society of the United States. And HSUS says that people—and therefore shelter adoption policies—must keep cats indoors.

Over forty years ago, the late Phyllis Wright of HSUS, the matriarch of today’s killing paradigm, wrote in HSUS News,

I’ve put 70,000 dogs and cats to sleep: But I tell you one thing: I don’t worry about one of those animals that were put to sleep: Being dead is not cruelty to animals.

She then described how she does worry about the animals she found homes for. From that disturbing view, HSUS coined a maxim that says we should worry about saving lives but not about ending them and successfully propagated this viewpoint to shelters across the country. For many agencies, the HSUS standard is the gold standard. It is not uncommon for shelters to state they are “run in line with HSUS policies.” Consequently, it’s very easy to surrender an animal to a shelter and very hard to adopt one because of a distrust of the public. And after turning away adopters, these shelters often turn around and kill the same animals.

In reality, most people care deeply about animals and can be trusted with them. Evidence of this love of animals is all around us: we spend $48 billion a year on our companions, dog parks are filled with people, veterinary medicine is thriving, and books and movies about animals are all blockbusters because the stories touch people very deeply. Nonetheless, HSUS blames the public and because it has significant influence over shelter policies, promotes this view through shelter assessments, national conferences, and local advocacy. Consequently, it has failed to educate shelters to take more responsibility for the animals entrusted to their care. As a result, HSUS has impeded innovation and modernization in shelters. The result: unregulated, regressive shelters slavishly following the protocols of HSUS based on an idea that no one can be trusted. The employee at Tompkins County’s SPCA embodied this attitude. Such people are not really worried about the remote possibility that the adopted cat would one day get hit by a car and killed; they kill cats every day—obviously, killing is not the concern. Instead, staff at the Tompkins County SPCA at that time—like many shelters—can simply say they are operating “by the book,” even though that meant unnecessarily killing animals every year in the process. In other words, I came face to face with mindless bureaucracy.

I challenged the Tompkins County SPCA shelter manager on this score, asking her how it made sense to kill cats today in order to save them from possibly being killed at some time in the future. “HSUS says,” she responded, “that in order to increase the number of adoptions, we have to reduce the quality of homes”—we must, as a staff member of HSUS once later quipped, basically “adopt Pit Bulls to dog fighters.” And that, she stated, is something we should not do.

Tragically, this is a commonly held misperception in the culture of animal sheltering, but the facts prove otherwise. Increasing adoptions means offsite adoption events, public access hours, marketing and greater visibility in the community, working with rescue groups, competing with pet stores and puppy mills, adoption incentives, a good public image, and thoughtful but not bureaucratic screening. It has nothing to do with lowering quality. It has absolutely nothing to do with putting animals in harm’s way. Indeed, shelter killing is the leading cause of death for healthy dogs and cats in the United States. Adoptions take animals out of harm’s way.

Moreover, successful high-volume adoption shelters have proved that the idea that one must reduce quality of homes in order to increase quantity is merely the anachronism of old-guard, “catch and kill” shelters that must justify high kill rates and low adoptions. Quality and quantity are not, and have never been, mutually exclusive. As one progressive shelter noted:

The best adoption programs are designed to ensure that each animal is placed with a responsible person, one prepared to make a lifelong commitment, and to avoid the kinds of problems that may have caused the animal to be brought to the shelter.

I agree. I have long been a proponent of adoption screening because I, too, want animals to get good homes. But truth be told, in shelters where animals are being killed by the thousands, I’d rather they do “open adoptions” (little to no screening) because I trust the general public far more than those who run many animal control shelters—those who have become complacent about killing and willfully refuse to implement common-sense lifesaving alternatives. In fact, I recently assessed a municipal shelter with poor care and a high kill rate in one of the largest cities in the country. They practice open adoptions and volunteers have long clamored for adoption screening. My recommendation was as follows:

This is an area where volunteers have repeatedly suggested some form of screening to make sure animals are not just going into homes, but “good” homes. This suggestion has some appeal. And while it should ultimately be the agency’s goal, in the immediate cost-benefit analysis, I think it would be a mistake to do so at this time. While the shelter should ensure potential adopters do not have a history of cruelty, the shelter is not capable of thoughtful adoption screening and the end result will mean the needless loss of animal life.

At this point in the shelter’s history, the goal must be to get animals out of the shelter where they are continually under the threat of a death sentence. And given the problems with procedure implementation at the shelter, the process will become arbitrary depending on who is in charge of adoptions. There is simply too much at stake for the staff I observed to hold even more power over life and death.

In addition, several high-volume, high-kill shelters have realized that denying people for criteria other than cruelty, would lead them to get animals (likely unsterilized and unvaccinated) from other sources, with no information or guidance on proper care, which the shelter can still provide.

When the shelter has high quality staff, is consistent in applying sound policies and procedures, and has achieved a higher save rate—when shelter animals do not face certain death—it can revisit the issue of a more thoughtful screening to provide homes more suitable for particular shelter animals.

Unfortunately, too many shelters go too far with fixed, arbitrary rules—dictated by national organizations—that turn away good homes under the theory that people aren’t trustworthy, that few people are good enough, and that animals are better off dead. Unfortunately, rescue groups all-too-often share this mindset. But the motivations of rescue groups differ from those of the bureaucrat I ended up firing in Tompkins County. People who do rescue love animals, but they have been schooled by HSUS to be unreasonably—indeed, absurdly—suspicious of the public. Consequently, they make it difficult, if not downright impossible, to adopt their rescued animals.

I recently read the newsletter from a local cat rescue group. There was a story about two cats, Ruby and Alex, in their “happy endings” section. Under the title, “Good things come to those who wait,” the story explained that Ruby and Alex were in foster care for 7 ½ years before they found the “right” home. I wondered what was wrong with the cats. If it took seven years to find them a home, surely they must have had some serious impediments to adoption. But I couldn’t find anything in the story. Under another section in the newsletter listing the cats in their care that still needed to find “loving homes,” I found the answer.

The first one I looked at was Billy. Billy was a kitten when he was rescued in 2001. He is still in a “foster” home. Does it really take 8 years to find the “right” home? Surely, I thought again, something is wrong with this cat. But Billy is described as “easy going, playful, bouncy.” It goes on to say that “Billy loves attention and loves to be with his person. Mild-mannered and gentle with new people, he’s also a drop-and-roll kitty who will throw himself at your feet to be petted.” They also note that he likes dogs. In other words, Billy is perfect.

Clearly, the pertinent question wasn’t: “What’s wrong with the cats?” The real question was: “What’s wrong with these people?” Not surprisingly, the rescue group does not believe families with young children should adopt. They claim that if you have children who are under six years old, you should wait a few years. In reality, this rule is very common in animal sheltering. But it is a mistake nonetheless. Families with children are generally more stable, so they are a highly desirable adoption demographic. They also provide animals with plenty of stimulation, which the animals crave. Children and pets are a match made in heaven.

So if families with children shouldn’t adopt, who does that leave? Unfortunately, this group also states that kittens ‘require constant supervision like human babies do.’ My family frequently fosters kittens for our local shelter. When fostering, we live our lives like we always do: we visit friends, take walks, dine out. We often leave home for hours at a time. Obviously, I would have never done that with my kids when they were babies. That isn’t a statement on loving children more than animals. A kitten can sleep, eat, drink, use the litter box, play with a toy, and more at only six weeks of age. A human baby would starve to death surrounded by food if left alone at that age. Kittens are not “like human babies.” They are more advanced, skilled, smarter, and cleaner. But that’s not the point. The point is that the “constant supervision” rule eliminates potential adopters who go to work, too, but would otherwise provide excellent, loving, nurturing homes. That leaves the two minority extremes: unemployed people and millionaires—although my guess is the former would be ruled out, too.

Having eliminated the two most important adopter demographics (working people and families with children), is it any wonder that Billy—an easy going, playful, cuddly, gentle, drop-and-roll kitty—has been in foster care for eight years?

A Pennsylvania rescue group, operating in a community where animal control kills most animals entering that facility, should be working feverishly to adopt out as many animals as possible so they can open up space to pull more animals from the shelter. Instead, they put up ridiculous roadblocks stating that “Cohabitating couples who have not married need not apply to adopt our pets.” Apparently, people have tried because they follow up by noting on their website that you should not waste your time trying because “there are no exceptions.” This eliminates many committed couples and, for those who live in states without marriage equality, most gay people.

And a rescue group from Louisiana, a state with some of the highest killing rates in the nation, pummels you with 47 reasons not to adopt an animal on their application, including the warnings that animals will “damage your belongings, soil your furniture and/or flooring, scratch furniture, chew and tear up items, knock down breakable heirlooms, and/or dig up your yard.”

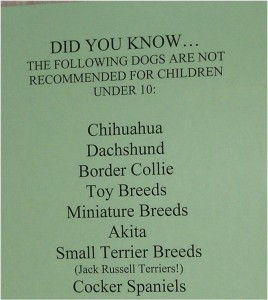

When I visited the humane society in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania a number of years ago, I was presented with a list of breeds considered not appropriate for homes with children under ten years old: Chihuahuas, Collies, Toy Breeds, and all small terriers.

Several years ago, this mentality really hit home—literally, my home. We decided to add another dog to our family. Having worked at two of the most successful shelters in the country, having performed rescue my whole adult life, having consulted with some of the largest and best known animal protection groups in the country, owning my own home, working from home, and allowing our dogs the run of the house, I thought adoption would be easy.

Adopting from our local shelter was not possible because we wanted a bigger dog which was against their rules because we had young children. Instead, we searched the online websites, and found a seven-year-old black Labrador Retriever with a rescue group about an hour south of us. I called about the dog and asked if we could meet him. They wanted to know if we had a “doggy door” leading to the backyard. We did not, but I told them happily—and naively—that I work from home and that we homeschool the kids, so the dog will be with us all the time. One of us will just let him out when he wants to go like we do for the resident dogs and then he can come back in. We have a fenced backyard. I housetrained every dog we ever had. No problem, I told them.

But that was not good enough. Apparently, the dog should be able to go in and out whenever he wants without having to ask. No doggy door, no adoption. “But,” I started to stammer: seven years old, larger black dog, sleep on the bed, with us all the time, fenced yard:. DENIED.

We then found another dog, a Lab-cross, with a different rescue group. About five years old, “a couch potato” according to the website. Perfect, I thought. I haven’t exercised since I was 18! I’ll take the dog for a walk around the block twice a day, but mostly will hang out, 24/7!

“We’d like to meet him,” I said when I called.

“There’s a $25 charge to be considered above and beyond the adoption fee,” they replied.

“No problem. If he likes our dogs, we’ll pay whatever it costs.”

“No,” I was told. “You have to pay the non-refundable fee before you can meet any dog and before we review your application.”

“What are your rules for adoption?” I said, not wanting to sink $25 if I was going to be denied because of the age of my kids, because I have brown eyes, or because I am balding.

“We can’t discuss that until after you pay the $25.”

Exasperated, I hung up.

We finally found a dog—a seven year old, lab-mix with a rescue group two hours from us by car. The fee was $250 to adopt, a pricey sum, but we were approved over the telephone because she was familiar with my work.

I could have given up. Lots of people do. When I tell people what I do for a living, that my work takes me all over the country trying to reform antiquated shelter practices, people constantly tell me how they tried to adopt from a shelter or rescue group, but were denied for entirely illogical reasons. One woman told me of her own failed attempt to adopt a dog and save a life. She owned an art gallery and wanted a dog who would come to work with her every day, just like her previous one who had recently died. The new dog would also have the run of both the house and office. She went to several shelters to adopt, but all of them denied her: she had really young kids and she wanted a large dog, and that was against the rules. She ended up at a breeder because she really wanted a dog, she said sheepishly, thinking I would judge her as having failed. “But I tried:” she trailed off. “The shelters failed you,” I replied.

Recently, HSUS launched a campaign to help shelters “educate the public” about adoption policies by creating a poster for shelters to hang in their lobbies. The poster features a chair beneath a light in a cement room. The tagline reads: “What’s with all the questions?” and it tells you not to take it personally. Rather than ask shelters to reexamine their own assumptions, HSUS produces a poster of what looks like an interrogation room at Abu Ghraib, instructing potential adopters to simply put up with it. In the process, adopters are turned away. Cats like Billy wait years for a home. And animals are needlessly killed: three million adoptable ones, while shelters peddle the fiction that there aren’t enough homes.

In fact, there are plenty of homes. The experience of successful No Kill communities proves it; No Kill communities now thrive across the United States. The data also proves it. Approximately three million dogs and cats that need a home are killed every year. Simultaneously, [of the 23 million people] looking to get a new dog or cat, [17 million] can be persuaded to adopt from a shelter. And, the number of people shelters turn away because of some arbitrary and bureaucratic process proves it. Like this experience shared with me a few years ago:

I tried to adopt from my local shelter: I found this scared, skinny cat hiding in the back of his cage and I filled out an application. I was turned down because I didn’t turn in the paperwork on time, which meant a half hour before closing, but I couldn’t get there from work in time to do that. I tried to leave work early the next day, but I called and found out they had already killed the poor cat. I will never go back.

Shelter animals already face formidable obstacles to getting out alive: customer service is often poor, a shelter’s location may be remote, adoption hours may be limited, policies may limit the number of days they are held, they can get sick in a shelter, and shelter directors often reject common-sense alternatives to killing. One-third to one-half of all dogs and roughly 60 percent of cats are killed because of these obstacles. Since the animals already face enormous problems, including the constant threat of execution, shelters and rescue groups shouldn’t add arbitrary roadblocks. When kind hearted people come to help, shelter bureaucrats shouldn’t start out with a presumption that they can’t be trusted.

In fact, most of the evidence suggests that the public can be trusted. While roughly eight million dogs and cats enter shelters every year, that is a small fraction compared to the 165 million thriving in people’s homes. Of those entering shelters, only four percent are seized because of cruelty and neglect. Some people surrender their animals because they are irresponsible, but others do so because they have nowhere else to turn—a person dies, they lose their job, their home is foreclosed. In theory, that is why shelters exist—to be a safety net for animals whose caretakers no longer can or want to care for them.

When people decide to adopt from a shelter—despite having more convenient options such as buying from a pet store or responding to a newspaper ad—they should be rewarded. We are a nation of animal lovers, and we should be treated with gratitude, not suspicion. More importantly, the animals facing death deserve the second chance that many well intentioned Americans are eager to give them, but in too many cases, are senselessly prevented from doing so.