One volunteer’s view of a shelter’s transition to No Kill

Guest blog by Valerie Hayes

The Tompkins County SPCA is located at 1640 Hanshaw Road in Ithaca, NY, but well outside of town. Many people know it from having read Redemption: the Myth of Pet Overpopulation and the No Kill Revolution in America. In Redemption, Nathan Winograd recounts the history of American animal sheltering and describes how, under his leadership, Tompkins County, NY became the first truly No Kill community in the entire United States. The inspiring story of its overnight transformation from overkill to No Kill has moved many to replicate its success. It has also infuriated others who have a vested interest in the status quo and its intrinsic failures, and they have alternately ignored and denied the accomplishment of ‘the little shelter that could’, and of the first community in the country to get sick and tired of death and to stop the killing.

I’ve read Redemption too, but it’s a little bit different for me. To me, the Tompkins County SPCA is more than a story in a book that I just happened to pick up off the shelf—I was there.

My perspective on No Kill is one of somebody who can look back on a story that has already played out, but who remembers that the struggle looked quite different when we were facing directly into it—back then the future of the TCSPCA was most uncertain and the struggle had no clear end in sight. There were turning points along the way—dangerous times when the wrong decision could have been made. There were many needless animal deaths and much heartache.

It was a shelter like so many others.

Prehistory

I had first volunteered at the TCSPCA in the early nineties, while I was in college. At that time, I never saw another volunteer. Apparently, I was the only one, and I was left to my own devices—ignored, basically. I came in every week and walked dogs or socialized the cats (who had to stay in their cages at all times) or did basic care. I’d worked in a veterinarian’s office and had learned how to give vaccines, check for and treat ear mites, and so forth. I bathed animals who were dirty and trimmed away mats on those with unkempt coats. At that time there were ample supplies of gallon bottles of shampoo and tubes of sticky beige ear miticide. The quantities of these things never seemed to vary between the times that I was there, as if I were the only one using them. The ear mite treatment would always leave the cats looking somewhat annoyed, with the sticky beige paste smeared on the fur around their ears. I look back and wonder if I hurt or helped what I now know was their slim chances of being adopted. I was often the only one working with the animals, as the staff congregated around the front desk socializing. Few potential adopters came through the shelter. I remember seeing the number of empty cages when it wasn’t “kitten season” and thinking to myself, “what if there was some way to shift animals around to alleviate crowding?” I remember wondering why “wild” cats were even brought to the shelter. They appeared to be just as capable as any raccoon of taking care of themselves. At the shelter, they had no chance.

It was a lonely place. My presence was barely acknowledged and I eventually stopped going.

2000

Several years later, in the spring of 2000, I decided to go back and the place was quite different. Volunteers were socializing cats and walking dogs, and there were several adopters looking at animals. The staff still largely congregated around the front desk, but the presence of the volunteers made the place different. There was a frantic edge to it, though, a certain desperate scurrying around—cleaning here, feeding there. The tension was pervasive and palpable.

The shelter now had an application for volunteers and I filled one out. No longer would I be allowed to vaccinate animals or administer first aid—certain things were not considered the purview of volunteers. There was some interesting talk, though—the shelter was “going no-kill”, but “wasn’t there yet”. There was something called “fostering”—volunteers could take animals, such as orphaned kittens, into their homes on a temporary basis until they were ready for adoption, and this would also take some pressure off of the shelter—its boundaries would be more elastic. There would be less need to kill for space. There was also a nationwide shortage of euthanasia solution, and leaders of national humane organizations were up in arms about this ‘crisis’ and the suffering it would cause. Shelters would be forced to release animals back onto the streets! They would kill in inhumane ways! They pushed for production to resume. What to do with all of those animals if you can’t kill them? Shelters would be helpless without their ‘blue juice’.

At the time, I had a very elderly cat with cancer, and I didn’t want to stress him by taking in kittens, but I decided that once he passed away, I’d honor his memory by fostering litters of kittens.

I volunteered in the cat room, socializing cats, cleaning litter boxes, and talking to people interested in adopting cats, and became only slightly acquainted with a few of the other regular volunteers. The building was small and poorly designed for housing animals. Dog walkers had to walk the dogs through the cat room to get outside, which meant that the cats were repeatedly upset throughout the day. The dog kennel area was intolerably noisy—an echo chamber for constant barking—I couldn’t stand it and it couldn’t have been any better for the dogs who had no choice and very sensitive hearing. I considered myself more of a dog person than a cat person but worked with the cats because the din in the kennel was more than I could take. In a room adjacent to the front desk was an intake area where animals were kept prior to being vaccinated or dewormed. A hallway area was used to house cats and sometimes small dogs not on public view—ferals and ones who were on their initial hold period. At the end of the hallway was the isolation room where sick animals were kept. They were supposed to be receiving nursing care. Volunteers weren’t supposed to go in there. Adjacent to the hallway was the garage, a rather large space not used to house animals, but which contained a fair amount of junk—broken cat carriers, bags of moldy food—items which should have been walked out front to the dumpster. This was where staff liked to take cigarette breaks while volunteers did the work they were being paid to do.

In late April, my beloved old cat Doikie passed away from his cancer. In early May, sick and tired of death, I adopted a skinny, deaf cat with some skin issues. She had come in as a stray and was pregnant, and I was told she was to be spayed, her kittens aborted, before I could take her home. I also filled out an application to foster kittens. The foster care application stated that animals had to be returned to the shelter for adoption—volunteers couldn’t just adopt them out. I agreed to that, as it was a precondition to fostering at all, and I didn’t know any better. It specifically asked if the applicant was willing to take their foster animals back if they were in danger of “euthanasia,” and if not, then why. I answered that I would absolutely take them back from the shelter if space was needed, no questions asked, in a heartbeat and at the drop of a hat.

After her surgery, I took my new cat home. I named her Lotus, hoping that something beautiful would grow out of the mess that she was, and it did. After a nasty bout of upper respiratory infection, she began to gain weight. The unsightly skin problems turned out to be due to a flea allergy and her poor nutritional state, and those soon cleared up. She was a very loving cat with a purr that could be heard in the next room with the door closed.

My first litter

I waited and waited to be assigned my first litter of foster kittens. I knew that it was “kitten season” And wondered what was taking so long? Why didn’t the shelter call me to foster? I’d see empty cages every week at the shelter though. It’s not like it was overflowing or anything. Maybe this “no kill” thing was working. I really didn’t know much about it. Finally, in mid-June I got a call that the shelter had a litter of orphaned kittens. Would I take them? Of course. I went to the shelter to pick them up. There were five kittens; all charcoal gray—four short-haired, one medium-haired. They were very healthy and about 4 weeks old, old enough to eat cat food and not require bottle-feeding, but too young to be adopted or in the shelter environment.

I took them home and set them up in a spare room. Within a couple of days, they were able to climb out of the large box I had corralled them in. They were very mobile. They played nonstop. Lotus, now fully recovered physically, showed an immediate interest in the kittens. She strode in to the room, gave me a look that told me that I was relieved of all duties except cleaning the litter box and keeping the food and water bowls full, and took over where their mother had left off, grooming them, instructing them in important cat things and generally supervising them. She was really in her element raising those kittens and lovingly tended them for the next month.

I took pictures of the kittens and put up a poster advertising them at each of my two jobs, making it clear that the adoption had to go through the shelter. I didn’t get any takers, but there were plenty of empty cages at the shelter. After a month, the kittens were old enough for their first vaccinations and to go back to the shelter for adoption. I called ahead of time to make sure that there was room. I wouldn’t want them taking up space needed by another animal. I was assured that things were fine, so I brought them in.

They got their shots and got set up in their cages. I reiterated that I would take them back if space was needed, and wrote that I would take them back, along with my contact information, on each of their forms. I bid my kittens farewell and hoped that they would be adopted into good homes quickly. I thought I’d done the right thing.

Death and the letter

By next weekend, a couple of them were gone. I checked the shelter’s logbook and confirmed that they had been adopted. I gave my remaining kittens some extra attention. They were looking good and staying healthy. The following weekend, all five were gone. Once again, I checked the logbook to see when they were adopted. Two of them had been killed. I never even received a telephone call or an email asking that I take them back. They had been perfectly healthy and loved and wanted, and they had a place to go if the shelter ran out of room. The shelter killed them. No phone call. Nothing.

I felt sick. The room began spinning. I was in tears. I’ll never forget the looks on the faces of the other volunteers. The staff didn’t budge. One other volunteer was concerned and tried to stop me from leaving, but I fled the building and somehow managed to bike the several miles home, even though I could barely see for crying. Before I left, he told me of a couple of other people who had recently had a similar experience. I passed some friends and didn’t stop to say ‘hello’.

I’m ashamed to say that my kittens died without names. I’d deliberately resisted naming them, because I knew I’d be giving them up, and I thought it would be easier. I now consider that a mistake. They should be known by names, not numbers.

Looking back on it, I have to think that the euthanasia solution ‘crisis’ of 2000 (and I subscribe to the definition of ‘crisis’ as being danger and opportunity) may have been the proverbial ‘shot in the arm’ for TCSPCA’s foster program and the reason why I even got my first litter of foster kittens. They had simply run out of the means to kill them. Evidently the ‘crisis’ had been resolved and it was back to business as usual.

At home, I tried to comprehend what had happened. The killing of my kittens was not an isolated incident. There is no such thing as an isolated incident. Not when matters of life and death are involved. If the shelter treated its own volunteers this way, if it talked about “going no-kill” at the same time as it killed needlessly, then it was suffering from dry rot. It had no core already. If this were to continue, then the animals of Tompkins County would truly have nothing. At the time, the slogan of the shelter was “We are a shelter of hope.” What hope was there? They killed healthy kittens with a place to go rather than make the simple phone call which would have gotten them out of there alive. It made me feel ill. “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” would have been more accurate. When I tried explaining to my family what had happened, I had to relate the story repeatedly before it sunk in. They couldn’t understand. It defied normal logic. An animal shelter killing kittens that a volunteer had cared for at home for a month rather than make a phone call? What?

I did not wish to become embroiled in an unproductive discussion with the powers-that-be behind closed doors.

No, this required an audience.

I crawled into bed with a note pad and pen and wrote a letter to the editor of the local newspaper, the Ithaca Journal. I wrote it in one draft and barely edited it. I stayed late after work the next day and typed the letter, proofread it, and then, like tossing a penny into a wishing well, clicked ‘send’.

No turning back now.

The editor acknowledged receiving the letter but would say no more. Those in authority at the shelter remained tellingly silent. I watched the paper every day, and over a week later, on Tuesday August 8, 2000, the letter ran as an op-ed piece alongside a weak and insulting response from the then-shelter director in which he failed to address a single point I’d made.

It was in print. My grief was now very public. Now what?

They were there all along

My call to remedy the situation was answered, not by the shelter, but by the community. People I knew expressed amazement at the situation, and support for me. When I arrived home from work, the red light on my answering machine was blinking furiously. It was full to capacity with messages from people expressing support for the position I’d expressed in the letter. Some were from people who I didn’t even know, but who’d been moved to look me up. Some told of their own experiences with the shelter.

Notably absent were any messages from the shelter’s executive director or anyone on the Board of Directors.

I’d gone to the shelter for my usual shift the weekend after they killed my kittens, knowing that they probably assumed and preferred that I just go away. No apology or comment from anyone on the shelter payroll, but then they didn’t throw me out either.

I went to the cat room and was greeted by a sight that would change everything. I consider it the first in a series of miracles I was privileged to witness. Another volunteer, one who had been present when I found out that my kittens had been killed, and who had wild hair like Einstein, stepped out from behind a bank of cat cages and told me in a low voice that there was going to be a meeting at the home of a couple of volunteers, invitation only, and I was invited.

He restored my hope.

The meeting was held soon after the letter was published. Over a dozen people were there. Our hosts had several dogs and cats who meandered through the meeting. We introduced ourselves and shared our experiences. Everyone had a piece of the puzzle. When put together, the picture of the shelter was worse than anyone alone had previously realized. Sick animals were being denied the medication that the veterinarian had prescribed for them (a veterinarian who was also a board member no less). Animals were being physically abused or not fed and watered. Complaints about abusive employees were ignored. Staff sat around socializing even as the shelter was filthy. Volunteers were treated with contempt, as if our only redeeming quality was that we did work the staff was paid to do, allowing them more time for cigarette breaks in the garage. Animals were killed despite available space. The list of specific incidents went on and on. We also learned that collectively, we had a lot of strengths and skills. We resolved to continue holding regular meetings and used email to keep in near-constant contact between meetings.

The shelter director had announced a meeting with the volunteers to take place at the shelter at the end of the week and we packed that stuffy little room. It was actually one of the very few times I’d seen him—mostly he stayed holed up in his office. He managed to make it very clear that gratuitous killing would not stop on his watch and that he was completely out of touch with reality. He was far too wishy-washy to discipline employees, much less fire them, no matter how much they needed firing. Who would he hire in their place? Who would want to work there? He harbored and protected animal killers and abusers. I would not be getting an apology from the person who killed my kittens, because that would mean revealing her identity.*

The shelter had a subsidized spay-neuter program called the Helen Milks Francis Fund, which had been established by and named for a citizen concerned about the unavailability of such services to those of low income. He told all present, almost boastfully, that it was “the best-kept secret in Tompkins County”. Unbelievable. Wasn’t it his job to make sure that it was not a secret?

One volunteer gritted his teeth when angry, a sound we would hear regularly over the next several months. That sound could be heard throughout the entire room.

The shelter director invited us to write suggestions and put them in his suggestion box, but we knew they would simply be ignored. They always were.

Eventually the meeting was over. People got up and began to leave. Another volunteer, a retired school teacher, led me back to the cat room to show me an emotionally traumatized white cat. She’d been there when I adopted Lotus and figured I must have a thing about white cats. This one was literally petrified. I picked him up and he remained statue-like, curled in a ball in exactly the position he’d been in while in his cage. I turned him over and he made no attempt to right himself or adjust in any way. After a couple of minutes of holding him, I thought I noticed a slight positive change. It was after hours and there was no one to handle paperwork, and anyway, I was fried, so I left him. I couldn’t stop thinking about him, though.

A couple of days later, I decided I had to adopt him. I went to the shelter and could not find him in the cat room. He wasn’t in the holding area or the hallway either. I started getting panicked. I went to the isolation room, and found him there. He’d gotten an upper respiratory infection. I was so relieved to find him still alive. I couldn’t go through a repeat of my experience with the kittens.

Not all of the employees were worthless. The person working in the isolation room was glad to see this cat, now named Blizzard, get out, and she gave me a few tablets of the antibiotic he was on to tide him over until I could get him a vet appointment. The volunteer who’d initially introduced me to Blizzard told me how a mentally disabled man had spent quite a bit of time holding and petting him. Apparently a local group home took residents on outings to pet animals at the shelter. (While I could wholeheartedly support a program like that in a place that was saving lives, I questioned the wisdom of bringing people who may be more emotionally vulnerable than most into a place where an animal they care for is likely to be dead by their next visit. It made me furious. At least that man could be truthfully told that this one got out alive.)

And, wonder of wonders, another employee, the one most sympathetic to volunteers, pulled me aside and, somewhat secretively, said she was sorry about the shelter killing my kittens, and could I possibly take in another litter because she had three tiny orphans that someone had just brought in.

Volunteers are not doormats, they are lightning rods. Forget that at your own peril

So, one week after the letter ran, I had come to adopt one traumatized cat, and ended up with one traumatized cat with a cold and three foster kittens. Whether the powers that be liked it or not, the foster program was continuing.

Never again would any foster cat of mine go back to the shelter. I’d learned my lesson. They got names, and they went to offsite adoptions. I stayed with them the entire time and would take them home again if they were not adopted.

Over the next few months, the ‘core group’ of volunteers, as we called ourselves, exercised our constitutional right to peaceful assembly by holding meetings in which we planned and strategized how to save more animals from the shelter. We would have liked nothing better than to be able to simply bottle-feed kittens and train dogs and hold offsite adoption events, but the shelter staff kept inventing new roadblocks for us to fight, recycling old roadblocks we thought we’d already defeated, and continuing to kill animals that had been spoken for. The faces of some of those animals are with me to this day.

The ‘core group’ self-assembled in an almost magical way. It had no real hierarchy. No one person had authority over anyone else, it was a much more of a cooperative, organic, ‘flat’ type of organization. We had various skills, whether it was keeping paperwork organized, making sure meetings ran efficiently with a predetermined agenda, setting goals to accomplish by the next meeting, coming up with creative ideas, negotiating with staff, communicating with the board, setting up adoption events, rehabilitating animals with behavior problems or illnesses, or coordinating a foster program. Different people took the lead in different areas. We were focused on one thing only—getting animals out of the shelter alive, and that, I suppose, is why things went as smoothly as they did—that and only inviting carefully selected people into the group.

The shelter wanted to discontinue the foster program, claiming that we might one day have a ‘run on the bank’ and all decide to bring our animals back to the shelter at once. We assured them that would never happen and outlined our plan for shifting animals around in the foster network if need be. They replied “but what if all the foster homes bring their animals back to the shelter at once?” No kidding. It was like talking to the wall. A local business owner who sold pet and garden supplies wanted to feature a couple of cats for adoption in his store. The shelter said ‘no,’ claiming that the cats might be neglected. Never mind that cats at the shelter were neglected all the time. We offered to have volunteers check on the cats a few times a week—we shopped there anyway. They still said ‘no’. The display cage donated to house cats at the store remained in its unopened box in storage at the shelter.

Complaints about animal-abusing staff were ignored. Complaints about staff tossing antibiotics in the trash and then marking down that they’d administered them to the sick animal for which they were prescribed were ignored. Animals that volunteers had put their names on, with a request that they be called, continued to be killed.

Apparently the negative publicity they had gotten for killing my kittens was irrelevant to them, as nothing changed.

The Ithaca Journal did a ‘Pet of the Week’ spot, sending a reporter and photographer to the shelter to feature an animal. On more than one occasion, the shelter killed the featured pet before the spot even ran, and people would come to the shelter wanting to adopt an animal who was already dead. Some staff members were very casual about stating how many animals they’d killed. During business hours, they mostly sat behind the desk, socializing, no matter how dirty the shelter was. The microchip scanner sat in a drawer, rarely, if ever used. One employee stole constantly, when he actually showed up for work. It was not so much a shelter for animals as a sinecure for the unemployable.

It was business as usual, except that they had us.

We took animals to offsite adoption events at local shopping malls and the farmer’s market and elsewhere. We found them homes. We explained to people who insisted that the shelter was No Kill, that it was not so. We had to do that regularly. It got to be quite aggravating. We fostered as many animals as we could, but with so few people willing to volunteer at a place like that, it wasn’t nearly enough. We did keep the program going, though. Some volunteers, with the means to do so, adopted animals outright and if staff was being difficult about fostering said animals. We snuck into the isolation room armed with canned cat food. The isolation room was technically off-limits to volunteers, but if we didn’t break a rule or two and go in to feed the cats, sick cats didn’t eat. A veterinarian on the Board had explained to staff that “food is medicine” to a sick animal, and they had to eat, yet they often went unfed. We socialized cats. We walked dogs. We handled adoption paperwork. We took verbal and emotional abuse.

Staff criticized us for being emotional, in an effort to dismiss our concerns. They had no real argument against our ideas or any of the plans we proposed, only the desire to continue as they always had. But what is the human-animal bond if not emotional? Neglect and senseless killing are bound to arouse emotion. How is that wrong?

Staff also accused us of having too much power. We actually had very little immediate power. Any power we had, we used to save animals. If we had more, we would have saved more animals. If we had still more, we would have hired better staff. Still more power, and that director and most of the Board would have been given the boot and with a great deal of pleasure. No, what we had was responsibility. We took upon ourselves responsibility for saving the animals at the shelter. The shelter’s Board, it’s director, and it’s staff had power, but wouldn’t take responsibility. That’s a really problematic dynamic, but unfortunately a common one in shelters. Responsibility without power is the fast track to frustration and burnout. Power without responsibility is a recipe for abject tyranny.

The situation wore on and on. Then, in November, several of us got an unexpected phone call from the Chair of the Board, an individual incapable of a statement that did not reek of politics. The shelter director had “tendered his resignation”. There was really only one way to interpret that—the Board had finally fired him. It had taken much too long, but they finally did it.

We were ecstatic.

What were they thinking?

But things were to get even worse before they got better.

The Board hired an interim shelter director who openly despised volunteers. Instead of being simply lazy and incompetent, he hated us. Among other things, he advocated keeping every other cat cage in the shelter empty, which would effectively halve capacity and increase the carnage, and he didn’t seem to know very much about animal care. He promoted to shelter manager an employee who, unfortunately, had an attitude much like his own.

We had to do something. The annual meeting was coming up and all paid members could vote. Those of us who were not yet members paid our dues. It galled me to give money to the shelter at that time, but I did it. The annual meeting was the scene of a showdown between the volunteers and the Board. We asserted ourselves. The belligerent interim director disappeared soon after, but his unfortunate legacy remained with us.

Words are deeds

The shelter had a subscription to Animal Sheltering magazine, published by HSUS. I am a compulsive reader, completely unable to resist the printed word, so when I saw copies of it lying around the front desk area, I’d naturally pick them up. They made for some mind-bending reading.

The November-December 2000 issue was astonishing. Its cover story was an Orwellian attempt to manipulate terms commonly used in reference to shelter animals, and included cartoons of animals objecting to the idea that they were rescued from a shelter and “explaining” various other terms. It mixed an exercise in rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic with failure to address the weightiest issue of all head-on. ‘Pet’ is objectionable, ‘guardian’ is preferred, but don’t call what shelters do ‘killing’. It deliberately misread the meaning of the term ‘no-kill community’ before that term was even in widespread use, setting it up as an impossibly utopian goal, and attempting to muddy the line between killing and euthanasia, a definition crucial to distinguishing No Kill shelters and the No Kill movement from places like the one where I was standing as I read this tripe. It treated the term no-kill as if it were something dirty, dishonest, related only to fund raising, or problematic, offensive, and likely to hurt someone’s feelings. The article was an attempt to turn simple terms into a sort of unintelligible slurry—able to mean anything and nothing at the same time.

It was accompanied by another article that blew my mind, a story about an animal control officer and his long career. It bemoaned how dogcatchers were hated, extolled him as a hero for animals and went on to describe how he’d ‘euthanize’ stray pets with hot car exhaust, by hosing them down and electrocuting them or by drowning them in buckets (birds, puppies and kittens). But it was all o.k., because he loved his cat, Tinsel.

Juxtaposed with the advertisements for crematoria, and the announcements for ‘hands-on’ “euthanasia” workshops, these articles left me nonplussed. I was still reeling from the killing of my kittens, even though I had to give the appearance of putting their deaths aside in order to continue.

Abusers will often kill or threaten to kill the pets of their abused, as a means of controlling them. I had enough perspective to see myself and the other volunteers as the shelter’s abused. The psychological dynamic was identical. What had I done? Shelters were fond of blaming the ‘irresponsible public’ for their killing. Was I “irresponsible” for taking in a litter of foster kittens? Why were they punishing us?

As bad as it was for us, the animals had it worse.

The January-February 2001 issue was openly hostile to the concept of animal rescue, and an article stated how the term ‘rescue’ was deeply offensive, reflecting badly on shelters, ignoring that the saving of a life is defined as ‘rescue’ by most people. Rule number one for rescuers is simple: Must not criticize.

It seemed as if one of the main purposes of this publication was to abuse language in an almost inconceivably ham-fisted manner. How could this go on? Could most readers not see through it? Apparently not. If it offered justification and cover for their killing, anything goes, however shoddy. Deception, including self-deception is a form of armor, at least for a time.Working with rescue groups is to be undertaken only with trepidation, and only on restricted terms. Lives were at stake, but false pride was more important. It is easier to blame others than to take responsibility.

The shelter’s own newsletter was a study in absurdity: an article on writing ditties about your cat from a place that systematically killed cats—was it a sick joke?

2001

In the New Year, the Board announced a nationwide search for a new director. Three candidates were invited for interviews, and a few volunteers were included in the interview process. They were impressed with one of the candidates. The other two they did not like, describing them as too friendly with the staff members who constituted some of the biggest problems at the shelter. They could make recommendations, but the hiring decision belonged to the Board.

Over the next several months, things continued to go from bad to worse at the shelter. One volunteer likened the shelter to the Headless Horseman. No one was leading it. The shelter manager wanted to micromanage every move of the volunteers, even as staff were allowed to sit around and socialize or treat the public rudely or allow animals to go unfed or without water or to keep the shelter dirty. She’d let the shelter run out of kitty litter or newspaper before she’d get off of our backs.

She instituted the infamous Sue Sternberg Temperament Test for the shelter’s dogs with devastating results. She used it as an excuse to kill many good dogs, while claiming that they were ‘unadoptable’. I suppose that this game-playing was to ingratiate her with the Board—they could claim progress towards No Kill, because she had found justification for killing in a plastic hand. At the time, I thought that she was misusing the test, but I subsequently learned that her use of the test was actually quite similar to the way its creator uses it. It is a test designed to justify killing. The dog volunteers were climbing the walls. We could not stop her and the Board refused to. The shelter seemed to be doing all it could to eradicate any credibility it may have had.

An elderly gentleman came in to adopt a dog. He selected one, a pointer mix, still on his mandatory stray holding period, hence not yet available. The man returned to the shelter the next weekend, eager to take his new buddy home. He’d picked out a name for his new dog and even bought a dog bed with the name embroidered on it. The employee behind the desk informed him matter-of-factly, that the dog had already been killed. I will not ever be able to forget the look on his face.

Among the reading material left lying around the shelter was a publication from California, a newsletter from a foundation I’d never heard of before. I remember standing in the lobby of the TCSPCA, in front of the desk as I read it. I can picture the room, the angle of the sunlight coming through the window, and where I was standing, perfectly. It told of a day when the entire nation would be No Kill. No shelter in the entire country would kill healthy or treatable animals. The author was even crazy enough to put a date on it and it would be within my lifetime. It seemed so incredibly impossible as to defy even imagining.

I hold that moment of ignorance perfectly preserved, as if in its own little snow-globe of memory, separated from all else–a silly toy that will one day be placed on a shelf to gather dust. I could not have known then that I was standing exactly where it would happen first.

Months passed. The toll of needless deaths continued to mount with no end in sight. What had come of the candidate search? When would the new director start? We heard nothing from the Board.

‘Kitten season’ was in full swing. Dogs continued to be “temperament tested” to death. The situation grew more and more desperate. I wondered if and when this new shelter director would materialize. The type of communication necessary for an organization to function well was notably absent from the shelter. Instead we had only that which tells you what you are dealing with.

Eventually, a member of the community became fed up with the mounting list of incidents attributable to the shelter manager, and she wrote a letter to the editor. It mentioned the shelter manager by name. The letter circulated among some of the volunteers before it was submitted to the paper, and a few of us signed onto it, including me.

That got me fired.

The other volunteers who had signed on went unscathed, but, as the shelter manager told me when she called first thing on the morning of Saturday, June 9, 2001, I was a ‘repeat offender’ and she’d thought I’d “learned my lesson”. She was appalled that I’d do such a thing to her. It was all about her. She ordered me to return the shelter’s “property”–my foster cats, immediately, or she’d come to my house to get them.

There was nothing she could have said to me that would have caused me more stress. I called one of my fellow volunteers—co-host of that first meeting, and grinder of teeth. He assured me that the Underground Railroad was ready to receive my cats if need be. I hopped on my bike, pedaled out to the shelter, and adopted my foster cats outright. The volunteer behind the desk, the one who’d introduced me to Blizzard, looked perplexed, but I couldn’t explain. I needed to get the completed adoption paperwork, and I needed to get the heck out of there.

The new director started the following Monday. Soon afterward, he held a meeting of the volunteers. He called and asked that I attend, having heard what had happened. I wondered to myself what the Board was going to inflict upon us this time. What new permutation of schmuckdom did they have in store? The meeting was well-attended. He had a lot of wrongs to right. He listened to what we had to say. He asked us to hit him with our toughest questions, and he answered them.

His predecessors had dug a very deep hole from which he’d have to haul the shelter.

Having been hurt so many times by the shelter, I was skeptical. I was not going to believe it until I saw it.

The first and only genuine apology I ever got for what the shelter did to my kittens, from someone in authority, came from someone who had been on the other side of the continent—3,000 miles away—when my kittens were taken from their cage and injected with sodium pentobarbital, from someone who likely had never heard of Tompkins County, New York at the time, and who would not have allowed something like that to happen. When I hear his critics call him ‘divisive’ and worse, I think of that. They have absolutely no clue what they are talking about.

I suppose that if this particular incident had happened to someone else, I would find it funny—getting fired from volunteering at a kill shelter for being critical of its killing two days before Nathan Winograd started as director and brought the killing to a grinding halt–but I got hit with a big slug of stress that day and I still can’t laugh. Maybe someday I will. The Old Guard is all about killing and abuse and power and lies, and a desperate gasp at the end of its reign is probably best appreciated if you know it for what it is at the time, or if you’ve gained a great many years’ distance on it.

A different world

The atmosphere at the shelter changed almost immediately. The amount of tension eased dramatically. When the killing stopped, even the worst of the employees eased up. The abuser of cats and tosser of antibiotic tablets relaxed and even smiled, but she thankfully did not last. She was too far gone. Her smiling would have been inconceivable just a couple of weeks earlier, but she did it and her face did not crack. If killing had never been an option at the shelter, would she have turned out differently?

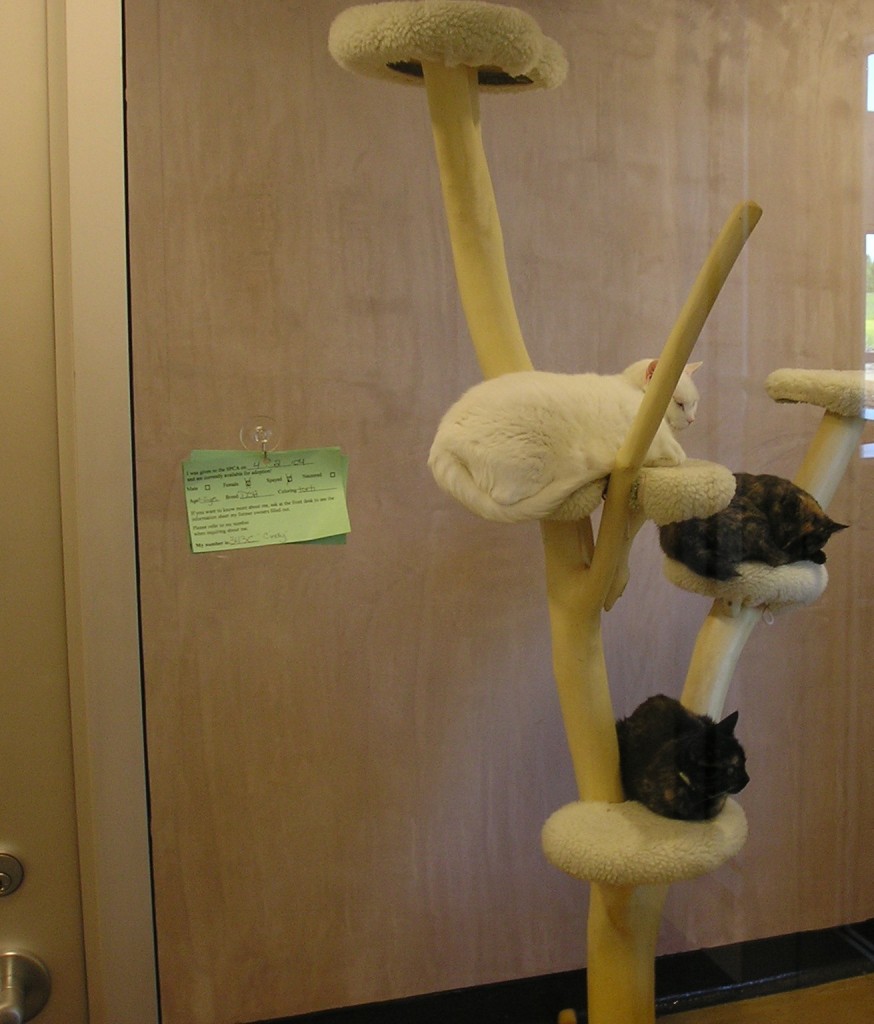

We now had breathing room. The new director dropped in on an offsite at the farmer’s market and complimented us on our professionalism. That was a first. The number of volunteers grew and grew. We were asked to foster animals on a daily basis. The shelter asked us, we didn’t have to fight and plead to get animals out. The place was cleaner. The animals got fed. Off site adoption events were more frequent. The Sue Sternberg Temperament Test was no longer used. The animals featured in the ‘Pet of the Week’ spot lived to be adopted. The display cage was unpacked from storage, and finally set up at the garden and pet supply store. We were no longer treated with contempt. I could finally, in good conscience, recruit others to volunteer at the shelter.

The staff from the bad old days was gradually replaced. Only a couple of them were able to make the transition. The shelter manager who’d fired me back in June remained, though she was stripped of any authority. She mostly stood around scowling at the volunteers, which was mildly amusing for a short while, but a waste of money. I’d seen a lot of positive changes, but remained skeptical. The shelter manager’s continued presence cast doubt on the shelter’s commitment to change, and was an ongoing insult to the volunteers. I later learned that when the new director was hired, the Board had ordered him not to fire her. She had their support. Knowing what I know now, I am amazed that the shelter succeeded at all. For them to support her was to reveal their total lack of respect for the shelter’s volunteers (or for their newly-hired director). We had given so much to the shelter. We were its heart and its soul. The new director persevered and built a case against her for six months. When he finally fired her, the long-time volunteers were jubilant. She was gone. Finally, she was gone.

The shelter was frequently featured in the local media. We had the use of a storefront in downtown Ithaca for the ‘Home for the Holidays’ adoption drive. Conventional “wisdom” said that shelters shouldn’t adopt out black cats around Halloween or any pets at all around Christmas. Those notions were discarded. Good riddance. The shelter sponsored spay-neuter events and courted the support of local veterinarians, and the Cornell Vet School, something it had not done before. It spayed or neutered all animals before they went home. It partnered with the North Shore Animal League, which took kittens to its facility in New York City for adoption, freeing up needed space and resources. The shelter built its capacity to save lives in various ways, even though it remained the same small, poorly designed building. The garage was renovated to house more animals rather than to store junk. It was worked to the max.

Eventually, it broke ground on land next door, and built a state-of-the-art pet adoption facility, a spacious ‘green’ building–LEED-certified, no less. After months of construction, it was finally ready and the animals were walked or carried next door. Once again, the atmosphere changed completely, and I don’t just mean the fresh air from the ventilation system. The first time I went to the new shelter, it was like a revelation. Many of the animals had been at the old building the previous week, but there are no steel cages in the Dorothy Park Pet Adoption Center, no bars of any kind. The animals are housed is small groups in more home-like settings. They were so much more at ease. Instead of seeing cats through steel bars or dogs from behind chain link, you see them through windows, as if they were waiting for you when you came home. The first glimpse anyone sees of the animals there is through the windows of their ‘condos’, and what a difference that makes. A dog or cat peers out of their condo window as you approach, and it is as if you are seeing them as you come home. Adopting? You’re halfway there.

Just a few years earlier, this would have defied imagining.

2013

When I hear someone deny that No Kill communities are possible, I think of a shelter in upstate New York, a place where one day it looked sickeningly hopeless, and the next day everything changed. It went through a crisis in the truest sense of the term—a dynamic and dangerous situation, and came to a turning point. Anything could have happened. If wrong decisions were made, the wrong leader chosen, if the volunteers had not united, if we hadn’t finally said “enough is enough” and meant it, the TCSPCA would not be what it is today. It would be what it was, and that would be tragic.

It got out of the habit of killing.

Its former incarnation was a place that killed animals and abused people. Had the volunteers not had each other to rely on, it would have chewed us up and spat us out one at a time. It was typical of what the American animal sheltering system has been allowed to become. But that place has been dead and gone for twelve years, and, in its place, an example and an inspiration for others to follow.

We live in a cruel, crazy world, one in which shelter killing is a habit, and getting to not killing requires a crisis.

We live in a beautiful world, because we can make the killing stop.

I believe in miracles.

They happen every day.

————-

* I subsequently learned that the person who killed my kittens without calling me was the very person who had given them to me to begin with. She was never disciplined for doing so.

This article was originally published by Valerie Hayes in the Examiner. It is reposted, in edited and amended form, with her permission.

For additional reading:

Valerie’s story and those of the other volunteers are part of a feature length documentary. Watch the trailer: