By Nathan & Jennifer Winograd

There is little reason why most people, your average animal lovers in the United States, would know pet overpopulation is a myth. The one fact that would dispel the myth is something they almost never see consistently because they do not go to shelters every day. But animal rescuers see it. Animal activists see it. And others in sheltering do also. They see it daily, but still believe in pet overpopulation. What do they see every time they go into animal shelters? They see empty cages. Shelters kill dogs and cats every single day, despite empty cages.

Empty cages mean less cleaning, less feeding, less work. Some shelter directors simply don’t care and do it for that reason. Others do it because they falsely believe that no one will adopt the animals anyway. Still others kill because they believe the cages will get full. And others—such as in Tompkins County before my arrival—require a certain number of animals to be killed in the morning to make room for the new animals they expect that day—animals who might or might not come, animals who might come after those animals killed could have been adopted, lost animals who might be reclaimed, thereby opening up space without the need to kill, animals who instead could have been transferred to rescue groups or placed into foster care.

The No Kill Advocacy Center‘s model shelter reform legislation, the Companion Animal Protection Act (CAPA), makes it illegal to kill animals if there are empty cages, unless those animals are irremediably suffering. It also makes it illegal to kill animals when those animals can share kennels or cages with other animals. An end to the convenience killing of savable animals was part of the Austin, TX No Kill Plan because the prior director killed animals routinely, even though a state inspection report noted hundreds of empty cages on any given day. Activists in Austin credit the moratorium as one of the key provisions which increased the save rate to around 90%.

Unfortunately, a lot of the opposition by local shelters and statewide animal control associations to CAPA centers around that very mandate. Tragically, the large national organizations which they look to for guidance share their view. As a result, even when they do not keep cages empty simply to reduce workload, traditional shelters still routinely kill animals to have cages “ready and waiting.” By contrast, not only do successful, open-admission No Kill shelters fully reject this policy, proving that in promoting such a policy, national and state sheltering organizations are endorsing killing out of sheer convenience rather than any sort of “necessity,” but, more to the point, it shows how little these groups and the shelters which follow this recommendation actually care about the lives of animals. They may claim that killing is a last resort, but that is a lie. How else can you explain a policy that clearly prioritizes having an empty cage over the life of the animal currently inside it?

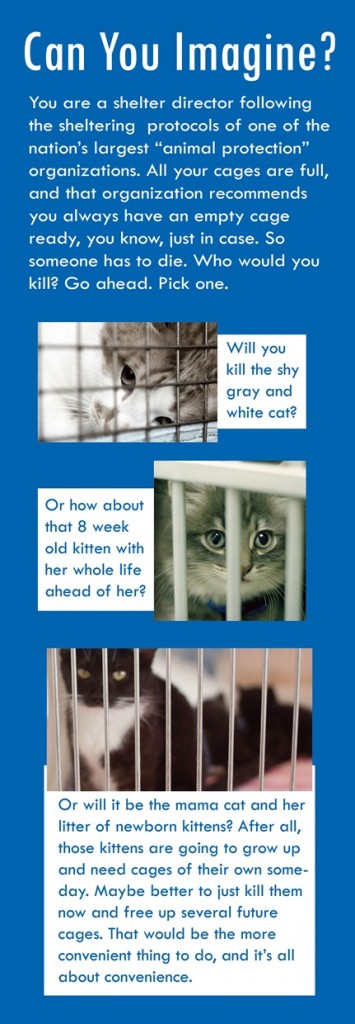

Now close your eyes and imagine you are a shelter director. All your cages and kennels are full, and it is your job to pick which animals die so you can have your empty cages for today’s intake. You enter the cat room and look around. Will you kill that black cat over there? How about that little orange tabby? Or what about that kitten making such a racket, sticking his paw outside the cage, begging for some attention? Yes, that little kitten has got to go. You instruct an employee to take him to the kill room, he gets excited thinking he is going to play. But this is what will happen to him instead, as described in a local newspaper,

A kitten with a hand gripping the scruff of [his] neck and a needle in [his] belly will squeal in terror, but once you’ve pulled out the needle and placed [him] back into a cage: [he] will shake [his]head and start to get on with [his] kittenish business. Then [he] starts to look woozy, and begins to stumble around. [He] licks [his] lips, tasting the chemical absorbed into [his] system. Soon, [he] becomes too sedated to stand. The animal collapses, and when [his] lungs become too sedated to inflate, [he] stops breathing.

Once you are done killing that kitten, you clean the cage so it can be ready (just in case an animal should need that cage when you open). Then it is on to the dog kennels. Who will die today? Will it be the little Jack Russell jumping up and down excitedly, hoping you might take him for a walk? What about that quiet, shy chocolate lab lying on his bed? Yes, how about him? And, again, you instruct a staff member to lead him to the kill room, and then clean that cage so it is ready for a dog that may or may not arrive. The dog looks up at you, shyly at first, but once the leash is on, he starts to walk with more confidence. He meets your eye and for the first time since he arrived, he looks, well, happy. He’s going for a walk. He’s going home. Of course, neither is true. Instead, you take him into a room, a room filled with the smell of antiseptic. If it is a regressive shelter, he’ll see the other dead dogs and start to panic and resist. But you’ll hold him down, or you’ll put a catch pole around his neck and drag him into the room. Either way, he’s going to die. You ordered him killed even though another dog might get adopted, also freeing up that cage these organizations tell you is necessary. Or maybe that dog’s person will arrive to reclaim him, ten minutes too late. Perhaps someone’s heart would have broken seeing how sad he looked, and chosen to adopt him, but, again, it’s too late for him now. He’s already dead, his body in the freezer, stacked on top of the large pile of dead dogs that were killed to make room for other dogs over the last few days, including the one that was killed to make room for him.

Then it on to the rabbits, then the gerbils, and the animals are dead, the cages are clean, and there they are, sitting empty and ready for the animals who will come through the doors. This is the status quo at kill shelters throughout the country. And just as it has broken your heart to read it, it breaks the heart of the employees that care. And that is why they leave. And those that don’t care, or who have become numb to the whole bloody mess, remain. And hence, the crisis of cruelty, caring and indifference that we have in shelters across the country, promoted and nurtured by the ruthless, heartless policies of our large, national “animal protection” organizations that preach preemptive killing for the animals coming in, who, in turn, will also face the needle in a few days.

Put aside the few minutes it takes to empty a cage and then clean it, what is the proof that this is needed? In fact, if animals need to be doubled up in a cage so that no one dies, that is what ethics and logic compel. And no one outside the professional sheltering world would ever think, for a moment, that that wasn’t the logical, ethical and proper thing to do. In fact, the suggestion that a shelter should kill an animal to free up a cage space that might or might not be “needed” would be met with horror by just about everyone who hasn’t been in the field long enough to become corrupted and accepting of what in truth are unethical policies totally divorced from the tragic reality they promote. In addition, preemptive killing for empty cages condones a total lack of commitment to creativity or hard work on the part of a shelter director. It is a shelter director’s job to come up with creative, life-affirming solutions. But if the animal protection movement gives them absolution to just do the easy and convenient thing—kill—then that is what they will do, each and every time. That is why we are in this mess of four million animals being killed in shelters to begin with. Killing is easy and killing is convenient, so why bother with the hard work of researching or implementing proven alternatives?

In fact, while you could ask the average person off the street to come up with 10 creative things you could do with the cat in the cage or the cat that might come through the door that does not involve the most extreme and inhumane response of all—killing—and they would not hesitate nor fail given what is at stake, ask the nation’s animal protection groups or statewide animal control associations to support a law requiring staff at “shelters” to do the same, and you’ll get a litany of excuses about why it is a bad idea. And worst of all, they will fight your efforts to require it. They will fear monger to the press and public, lie to legislators, and do everything in their power to make sure that the scenario you just read about above continues unabated—day in, day out—at shelters across this country. Why? Because they just don’t care.