There is no question that the effects of hoarding are tragic: animals wallow in their own waste, are denied food and water for long periods of time, do not get necessary veterinary care, are sometimes crammed into cages and do not receive walks or regular exercise, all of which results in tremendous suffering and death. Hoarding is cruel, painful, and abhorrent. But what does it have to do with rescue access laws and the No Kill movement? The answer is, not much. Nonetheless, it is a card those that are opposed to such laws like to play, as part of their fear mongering to defeat them. Their real concern is not the animals (if it was, they wouldn’t be neglecting and abusing the animals themselves or putting them under the constant threat of a death sentence). Instead, they are opposed to empowering rescuers who would be protected as whistle blowers if the laws are passed. Without such laws, rescue groups are afraid to complain about inhumane conditions or practices at shelters because if they did complain, they would not be allowed to rescue animals, thus allowing those inhumane conditions to continue.

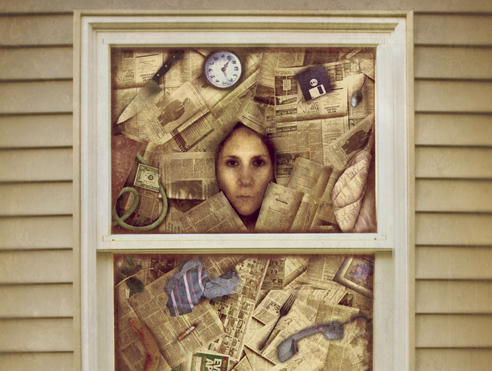

Unfortunately, when hoarding cases are brought to the attention of authorities and these cases make the news, some hoarders claim to be “No Kill shelters” or “animal rescuers” as a means of escaping culpability. And the groups opposed to rescue rights laws exploit that. In reality, however, hoarders have nothing in common with true animal rescuers, individuals who have founded non-profit organizations, who must report annually to the Internal Revenue Service, their state’s Attorney General, and often a State Department of Charities bureau. They have a Board of Directors which oversees them, they maintain a network of volunteer foster homes, and make animals available for adoption to the public, unlike hoarders who refuse to let their animals go. Non-profit rescue organizations seek to provide animals with care that is the opposite of that inflicted on animals by hoarders; and often inflicted by shelters themselves, which are rife with neglect, abuse, and killing as well. (Imagine a place where animals do not get fed. Imagine a place where animals with painful injuries do not get the veterinary care they need. Imagine a place where animals are stuck in cages and forced to wallow in their own waste. Imagine a place where the animals’ food is dirtied by cat litter and even fecal material. Imagine a place filled with dead and dying animals simply discarded in the garbage. These behaviors are the textbook definition of hoarding, but they also adequately describe conditions animals across this nation must endure when they enter their local “shelter.”)

But that has not stopped organizations such as PETA, the Humane Society of the United States, the ASPCA, and others from protecting these shelters by making the argument that rescue groups are nothing more than hoarders in disguise in order to oppose the rescue rights laws currently pending in states across the country, which would make it illegal for shelters to kill animals when rescue groups have offered to save them. They propose continued killing (the final solution) to a problem (rescuers might be hoarders) which, it turns out, isn’t really the problem.

Animal hoarding is the result of mental illness and is not as common as many animal protection organizations would have us believe. Psychologists estimate that only 2% of the population suffers from hoarding, and of those, not all of them “collect” animals—many collect inanimate objects. By contrast, killing is endemic to animal shelters in the U.S. In fact, killing is the number one cause of death for healthy dogs and cats in the United States. At your “average” shelter, an animal has a 50% chance of being killed, compared to the rare chance of ending up with a hoarder. Of course, in places like Memphis, Tennessee, the odds are more extreme: as high as 80%. And when it comes to animals which are sent to rescue, they all have a 100% guarantee of being killed because rescue groups are only empowered to save those animals scheduled to be killed. So, there is a 100% chance the animal is killed vs. a slim to none possibility, they’ll end up with a hoarder. Is it really a difficult decision?

To suggest that we must protect animals from rescuers is backward thinking. If we care about saving animals, we must save them FROM shelters by putting them in the hands of RESCUERS. Moreover, logic and fairness—both to rescuers and the animals—demand that altruistic people who devote their time and energy to helping the animals who end up in our nation’s shelters stop being equated with mentally ill people who cause them harm. Animal rescuers seek to deliver animals from the type of cruelty and abuse that characterizes not only the care or lack thereof given to animals by hoarders, but, in reality, by many of our nation’s shelters as well.

Despite such fear mongering over a decade ago when California was the first state in the nation to consider such legislation, that provision has been an unqualified success, increasing the number of animals saved, without the downsides opponents claimed. Indeed, coupled with other modest shelter reforms, the number of dogs and cats killed in California shelters dropped from over 570,000 animals the year before the law was passed to roughly 328,000 the year after, a decline of almost 250,000 dogs and cats. And, the number of small animals saved, such as rabbits, also spiked according to an analysis by one of the largest law firms in the world. Indeed, that analysis not only concluded rescue rights in California was incredibly successful, it concluded such laws were necessary in other states.

Despite the fact that killing in shelters is so common and hoarding so rare, nonetheless the various bills and laws that make it illegal for shelters to kill animals when rescuers are willing to save them have plenty of safe guards. These laws often exclude organizations with a volunteer, staff member, director, and/or officer with a conviction for animal neglect, cruelty, and/or dog fighting, and suspends the organization while such charges are pending. In addition, the bills pending in the U.S. this year require the rescue organization to be a not-for-profit organization, recognized under Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3). As a result, they must register with the federal government, and with several state agencies, including in some cases, the Department of State, the Attorney General’s Office, and Department of Agriculture Division of Consumer Services, providing a number of oversight and checks and balances.

In fact, statewide surveys have found that over 90% of survey respondents who rescued animals but were not 501(c)(3) organizations would become so if this law passes, effectively increasing oversight of rescue organizations if these laws passed. Moreover, some of these laws specifically allow shelters to charge an adoption fee for animals they send to rescue organizations, which would further protect animals from being placed in hoarding situations. And, in New York, the bill would empower shelters to investigate these groups if there is reasonable suspicion to believe that there is neglect or cruelty going on. Finally, nothing in these laws require shelters to work with specific rescue groups. They are free to work with other rescue organizations if they choose and they are also free to adopt the animals themselves. What they cannot do, what they should not be permitted to do, is to kill animals when those animals have a place to go.

It is simply unethical to condone animals having a 100% guarantee of being killed because there is a rare possibility they might end up with hoarders. No one who cares about the lives of animals would believe that to be otherwise. So the conclusion is inescapable: the organizations that fight these bills are led by individuals who, quite simply, do not care. But if they do not care about animals, they should care about money. In the City and County of San Francisco, the cost savings associated with less killing and more live outcomes by partnering with rescue groups topped $450,000 in just one year. And that should appeal to even the small-minded, hard-hearted bureaucrats who run animal protection organizations for what appears to be one purpose and one purpose only: to make as much money as possible by hoarding the money meant to save animals. Or, as Captain Jack Sparrow says, to take what they can and give nothing back.

Not all pirates sail the seven seas.