Excerpted from Friendly Fire by Nathan & Jennifer Winograd.

The law would have been simple. Senate Bill 359, a bill pending in the Virginia legislature in 2012, would have clarified that neutering and releasing feral cats back to their habitats was not illegal, allowing cat advocates to continue doing so without fear of prosecution. But PETA successfully led the effort to oppose the law, joining kill shelters throughout the state and the Virginia Animal Control Association in defeating it.

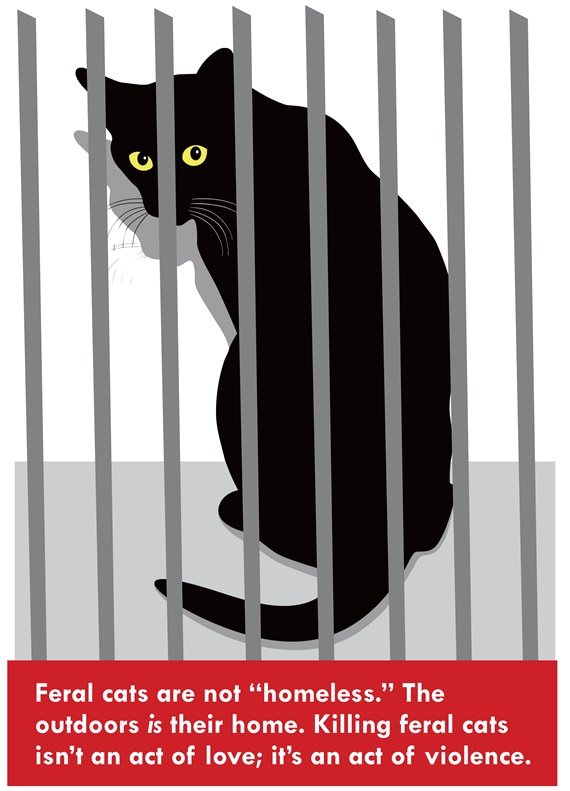

While cats as a whole face a roughly 60 percent chance of being killed in shelters, when those cats are “unsocial,” the percentage becomes nearly 100 percent. At shelters across the country, without TNR, every unsocial cat is put to death. And groups like PETA believe this is as it should be. According to these and other groups, cats belong in homes or they should be killed. To these organizations, the practice of TNR is setting the cats up for a lifetime of suffering, a claim which they and others use to round up and exterminate thousands of healthy and happy cats every year in communities across the country.

But is it true? In fact, it is not. Several studies confirm that from the cat’s perspective, the great outdoors really is great. A comprehensive 11-year study of outdoor cats found that they had similar baselines in health, disease rates and longevity as indoor cats. A subsequent study gave feral cats “A+” grades across a wide range of physical and health characteristics. In yet another study, less than one percent of over 100,000 feral cats admitted to seven major TNR programs across the United States were killed for debilitating conditions; while a fourth survey across 132 colonies of cats in north central Florida showed that 96 percent of the cats had a “good” or “great” quality of life.

And yet, even if it were true that these cats were disproportionately suffering outdoors, it would not change what the ethical response should be. It is never okay to kill an individual cat based on a group dynamic. If we were to postulate, for the sake of argument, that most feral cats die prematurely due to disease or injury, it would still be unethical to kill any individual cat because not only do that cat’s inherent rights ethically prohibit it, but we would never know if that particular cat will ever succumb to such a fate, let alone when.

Moreover, even if we did, even if we knew that a cat would get hit by a car two years from now, it isn’t ethical to rob him of those two years by killing him now. In the end, the answer from opponents of TNR programs—that we should stop cats from being killed by killing the cats ourselves—is a hopeless contradiction. But the contradiction goes even deeper.

While traditional shelters argue that all cats are the same, need the same things (namely, an indoor home), and should be treated the same because they cannot live outside, they themselves hold feral cats to a different standard. Once in the shelter, a “friendly” cat may be deemed suitable for adoption, while an “unfriendly” cat, by contrast, is killed outright, in some cases within minutes of arriving because they conclude such cats are “unadoptable” or unsuited for life inside a human home.

Biological Xenophobia

While some groups oppose allowing feral cats to live out their lives by arguing it is “for their own good,” others do so because they argue that cats are decimating bird populations and therefore deserve to die. Not only does the science contradict these claims,* but the idea that some animals have more value than others comes from a troubling belief that lineage determines the value of an individual animal. This belief is part of a growing and disturbing movement called “Invasion Biology.” The notion that “native” species have more value than “non-native” ones finds its roots historically in 1940s Germany, where the notion of a garden with native plants was founded on nationalistic and racist ideas cloaked in scientific jargon. This is not surprising. The types of arguments made for biological purity of people are exactly the same as those made for purity among animals and plants.

In the United States, Invasion Biologists believe that certain plants or animals should be valued more than others if they were at a particular location “first,” although the exact starting point varies, is difficult to ascertain and, in many cases, is wholly arbitrary. Indeed, all plants and animals were introduced (by wind, humans, migration or other animals) at some point in time. But regardless of which arbitrary measure is used, Invasion Biologists ultimately make the same, unethical assertions that “introduced” or “non-native” species are not worthy of life or compassion. They conclude that these species should be eradicated in order to “restore” an area to some fixed point in the past.

Nature, however, cannot be frozen in time or returned to a particular past, nor is there a compelling reason why it should be. To claim that “native” species are somehow preferable than “introduced” species equally or better adapted to a changing environment ignores the inevitable forces of migration and natural selection. All animals have a right to live, regardless of how and when they arrived or were “introduced.” Their rights as individuals supersede our own human-centric preferences, which are often based on arbitrary biases, subjective aesthetics or narrow commercial interests.

Moreover, no matter how many so-called “non-native” animals (and plants) are killed, the goal of total eradication can never be reached because, quite simply, nature is not static, nor is it possible to force it to become so. To advocate for the eradication of feral cats is not only cruel and unethical, it is to propose a massacre with no hope of success and no conceivable end.

Equally inconsistent in the philosophy of Invasion Biology is its position—or, more accurately, lack of a coherent position—on humans. If one accepts the logic that only native plants and animals have value, human beings are the biggest non-native intruders in the United States. With over 300 million of us altering the landscape and causing virtually all of the environmental and species decimation through habitat destruction and pollution, shouldn’t Invasion Biologists demand that non-native people leave the continent? Of course, non-profit organizations that advocate nativist positions would never dare say so, or donations to their causes would dry up. Instead, they engage in a great hypocrisy of doing that which they claim to abhor and blame “non-native” species for doing: preying on those who cannot defend themselves.

In addition, it is not “predation” that Invasion Biologists actually object to. Animals prey on other animals all the time without their objection. In fact, they themselves prey on some birds by eating them, and they prey on animals they label “non-native” by eradicating them. For Invasion Biologists, predation is unacceptable only when it involves an animal they do not like. And when it comes to animals they do not like, animals who do not pass their narrow litmus test of who is worthy to live and who should die, the cat stands at the top as “Public Enemy No. 1.”

Teaching Tolerance, Respecting Diversity

The ultimate goal of the environmental movement is to create a peaceful and harmonious relationship between humans and the environment. To be authentic, this goal must include respect for other species who share our planet. And yet, given its alarming embrace of Invasion Biology, the environmental movement has violated this ethic by targeting species for eradication because their existence conflicts with the world as some humans would like it to be. Condemning animals to death because they violate a preferred sense of order does not reject human interference in the natural world as they claim; it reaffirms it. And in championing such views, the movement paradoxically supports the use of traps, poisons, fire and hunting, all of which cause great harm, suffering and environmental degradation—the very things they ostensibly exist to oppose.

Over the last 250 years, the story of humanity has been the story of the human rights movement—of overcoming our darker natures by learning tolerance for the foreign and respect for the diverse. In the early 21st century, these are the cherished ideals to which humanity aspires in our treatment of one another. And yet when it comes to our relationship with other species, these values are turned on their head, and environmentalists—the very people who should be promoting tolerance and compassion for all Earthlings regardless of their antecedents—are instead teaching disdain for some, leading the charge to kill them and turning our beautiful, natural places into war zones and battlefields. We need a different, more humane and more responsible way of seeing the world and our place in it.

For in the end, not only is it wrong to label any species an “alien” on its own planet and to target that species for extermination, but it is also breathtakingly myopic. On a tiny planet surrounded by the infinite emptiness of space, in a universe in which the anomaly of life renders every blade of grass, every insect that crawls and every animal on Earth an exquisite, wondrous rarity, it is quite simply inaccurate to label any living thing found anywhere on the planet which gave it life as “alien” or “non-native.” There is no such thing as an “invasive” species.

We must turn our attention away from the futile and pointless effort to return our environment to the past toward the meaningful goal of ensuring that every life that appears on this Earth is welcomed and respected as the glorious, cosmic miracle it actually is.

***

For most of the history of animal sheltering in the United States, feral cats who ended up in shelters faced an almost certain death sentence. Without a human address, there was no one to reclaim these animals. Fearful of humans, they were not considered candidates for traditional adoption and were not afforded the opportunity. Combined with the misconception that they disproportionately suffer without human caretakers because they belong in homes, the tragic result has been the execution of virtually all healthy and self-sufficient unsocial cats in shelters across the nation. Such killing was the status quo until roughly 30 years ago, when cat lovers finally said “Enough!” and began advocating for the alternative of neutering and releasing them back into their habitats, a program called TNR.

In a TNR program—an essential component of the No Kill Equation—any feral cats who end up in the shelter are neutered and released back into their habitats. The shelter also works with local feral cat caregivers who trap community cats for spay/neuter. Sometimes, these cats have human caretakers who watch over them and feed them. But often, feral cats who end up in shelters are like other “wild” animals, thoroughly unsocialized to humans, surviving on their own through instinct and wit and no worse off because of it.

Many shelters argue that since cats are “domestic,” the unsocial cat without a human home is better off taken to a shelter and killed. These groups argue that a free-living cat’s life is a series of brutal experiences and shelters need to protect the cat from continued and future suffering. Not only does this fly in the face of actual experience and virtually all scientific analysis, even if it were true, the reality is that all animals living in the wild may face some hardship—and wild cats are no exception. But they also experience the joys of such a life, as well. Life, by its very definition, is a mixture of happy and sad, easy and hard. Since animal groups do not support the trapping and killing of other wild animals—raccoons, mice, fox—why do they reserve this fate for feral cats?

If feral cats are genetically identical to wild animals, and they survive in the wild like wild animals, and they are unsocial to humans like wild animals and if they can and do live in the wild like wild animals, shouldn’t they be treated like wild animals—with animal protection groups advocating on their behalf, pushing for their right to life and respecting and protecting their habitats? And, more importantly, why should any of them be condemned to death because of the sloppy logic that some may face hardship?

Of course, this inevitably begs the question, if feral cats are wild animals, why the special treatment? Why alter them? Why vaccinate? In such circumstances, sterilization and vaccination against rabies is necessary for several reasons. Not only does it eliminate the chance of future offspring ending up in the shelter, but because feral cats often live in close proximity to humans, it also eliminates behaviors associated with mating that have the potential to cause friction and intolerance. This is important given that the historic solution to such conflicts has been to trap and kill the cats. Moreover, because of decades of unsubstantiated fear mongering by animal protection organizations about the health risks associated with feral cats, vaccination is a way of addressing any perceived concerns of local health departments or regressive shelter directors, which exist even though feral cats pose virtually no health or safety risk to humans. Finally, once in the shelter, TNR is the functional equivalent of adoption. Spay/neuter isn’t the most important variable. The most important part of the TNR equation is the “R.”

Through TNR, cat advocates have found a life-affirming way to address the dogmas which the animal protection movement itself created and expounded for decades that have been responsible for the mass slaughter of unsocial cats. Right now, TNR-ˆis the most humane option for feral cats because it assures their safety and buys them a ticket back home.

***

***

For further reading:

—————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

My Facebook page is facebook.com/nathanwinograd. The Facebook page of my organization is facebook.com/nokilladvocacycenter. Many people mistakenly believe that the Facebook pages at No Kill Nation and No Kill Revolution are my pages. They are not.