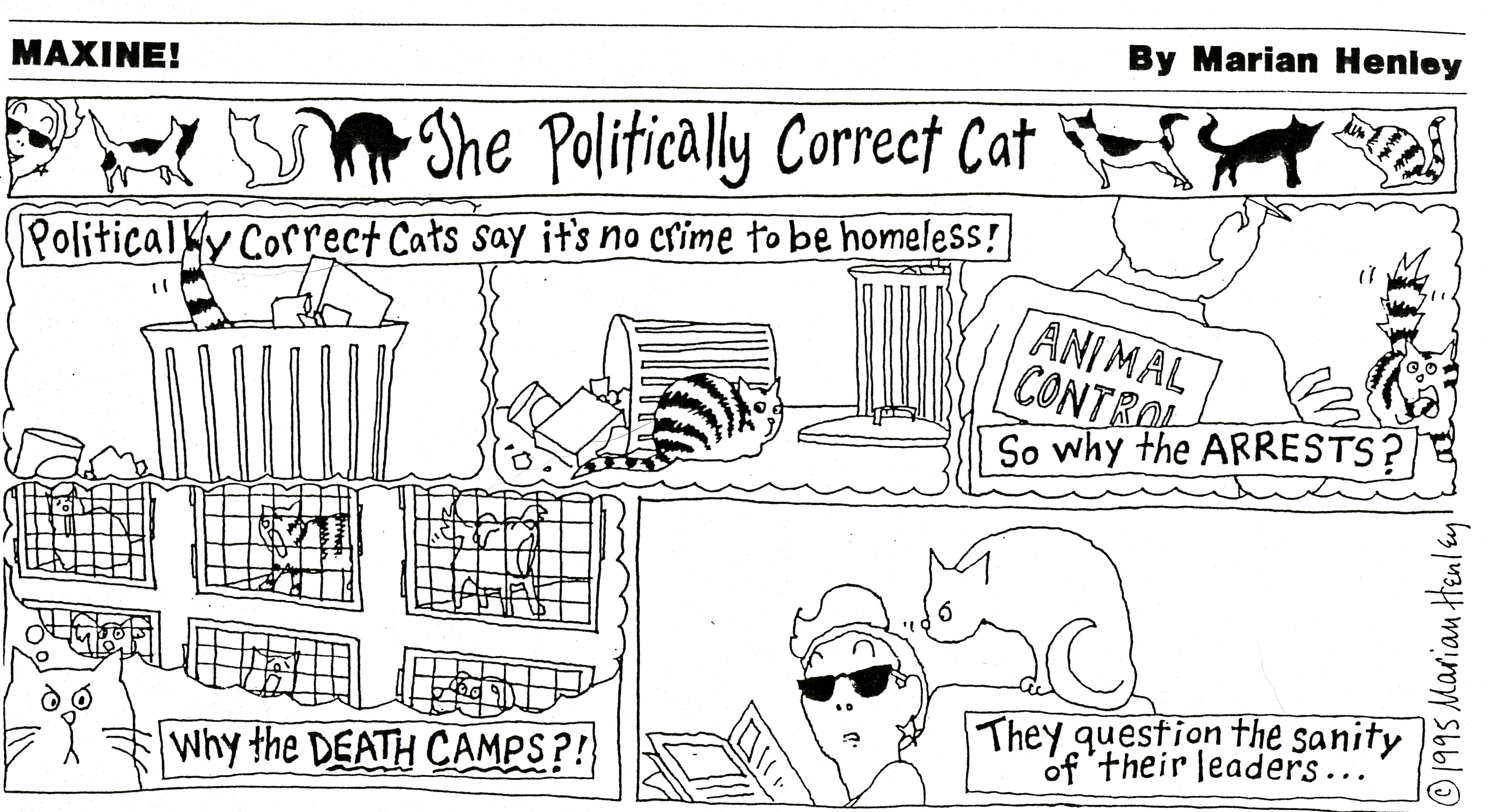

Our shelters can and should be the safe havens we want them to be. And we are not stuck in having to choose between a No Kill nation and what we have now, a system of death camps where animals are abused and then lose their lives by the millions. Nor do we have to choose between giving all animals away on the street and killing them. Nonetheless, I ask you to join me in a thought experiment.

One of the primary goals of my recently released book, Friendly Fire, is to expose the fallacy which our nation’s large animal protection groups have perpetuated for decades: the myth that our nation’s shelters are a network of compassionate safe havens for homeless animals. As the movement to end shelter killing has grown in size and sophistication, the networking made possible through the internet and social media has allowed animal lovers to connect the dots between individual cases of animal cruelty and neglect in shelters nationwide. These incidents reveal a distinct pattern. Animal abuse at local shelters is not an isolated anomaly caused by “a few bad apples.” The stunning number and severity of these cases nationwide lead to one disturbing and inescapable conclusion: our shelters are in crisis.

Frequently overseen by ineffective and incompetent directors who fail to hold their staff accountable to the most basic standards of humane care, animal shelters in this country are often poorly managed houses of horror, places where animals are denied basic medical care, food, water, socialization and are then killed, sometimes cruelly. The first time many companion animals experience neglect and abuse is when they enter the very place that is supposed to deliver them from it: the local animal shelter.

And yet in spite of this, many people, animal activists included, tenaciously assert that homeless animals are better off entering traditional kill shelters than otherwise. They buy into the rationalization long perpetuated by shelters that killing is not the ultimate form of harm, but rather, allowing animals to be at the mercy of an unkind and uncaring American public. But is it true? In fact, when emotions and traditional dogma that support this point of view are weighed against evidence, it is not.

Consider this: a shelter in one of America’s major cities commits the ultimate form of violence on cats. It kills them. In fact, it kills almost all of them. Roughly eight out of 10 cats are put to death. There is a lot the shelter could be doing to reduce that number: offsite adoptions, adoption marketing and promotion, foster care, a more robust relationship with rescue groups, and more. It refuses. In fact, when people do come to adopt, the presumption is that they cannot be trusted unless they prove otherwise. Their rules are arbitrary.

Not too long ago, the Humane Society of the United States, the flagship of the catch and kill sheltering establishment, launched a campaign to help shelters “educate the public” about adoption policies by creating a poster for shelters to hang in their lobbies. The poster features a chair beneath a light in a cement room. The tagline reads: “What’s with all the questions?” and it tells you not to take it personally. Rather than ask shelters to reexamine their own assumptions, HSUS produces a poster of what looks like an interrogation room at Abu Ghraib, instructing potential adopters to simply put up with it. In the process, good homes are turned away and animals are needlessly killed, while shelters peddle the fiction that there aren’t enough homes.

HSUS will tell you that it is important not to reduce the quality of adoptive homes, but this is just a smokescreen, a way to give shelters political cover for low rates of adoption and consequently high rates of killing. Indeed, no one could reduce the quality of adoptive homes more than HSUS itself, which lobbied to allow Michael Vick—a sadist who enjoyed beating dogs to death, hanging dogs, drowning dogs in buckets, shooting dogs, repeatedly slamming them to the ground, burying them alive, and attaching jumper cables connected to car batteries to their ears and then throwing them in a swimming pool—to get a dog. If HSUS believes Vick would make a good dog owner, who wouldn’t they consider qualified?

But let’s go back to our shelter with an 80% kill rate for cats. Dr. Michael Moyer runs the shelter medicine program at the University of Pennsylvania. In one of his lectures, he asks his students whether they think most people care about animals or abuse them. The question is a no-brainer and the answer, of course, is the former. All the data point to that direction: spending on companion animals is the eighth largest sector of our economy, it exceeds $50 billion annually, and it continues to grow even as other sectors decline. More than that, the success of No Kill around the country in over 200 cities and towns across America, the sheer number of animals who share our homes, and so much more tell the same story. Given that, he asks his students, wouldn’t it be more ethical for a shelter which kills 80% of the cats to simply go out to popular areas of the community and simply hand the cats to people, give them away, no questions asked. (A question I would follow up with is, Wouldn’t it be better for the animals if, given the way they are currently operating, that shelter didn’t exist at all?)

The students, of course, are horrified. Indeed, Google “Free to a Good Home” and you’ll get a litany of articles about the “high cost” of “free to good home,” mainly the threat that you may be putting animals in the hands of people who will harm them. But if the worst thing that could happen to them if we gave them away is the very thing that will happen to eight out of 10 of them if they stay at the shelter, is the cost-benefit analysis even close? If the cats stay at the shelter, eight out of 10 will be poisoned to death. That’s an 80% chance of harm. If they go out into the community, won’t it be less than that, Dr. Moyer asks? The answer of course, is yes. From the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine to the ASPCA, from Maddie’s Fund to the experiences of shelters across the country, every study that has looked at the issue has concluded that waiving adoption fees—in other words, giving the animals away for free—does not impact either the quality of the quantity of the adoptive home, but does increase the number of lives saved.

Of course, there is a lot shelters could be doing short of Dr. Moyer’s hypothetical. I have long been a proponent of adoption screening because I, too, of course, want to ensure animals get the best homes possible. But in shelters where animals are being killed by the thousands, and where they are horrifically neglected and abused in the process, I’d rather they do “open adoptions” if it means getting more animals out of there and doing so quicker because in truth, there is no greater threat to companion animals in this country than the so-called “shelter” in the community where those animals reside. Shelter killing is the leading cause of death for healthy companion animals in the U.S.

Dr. Moyer, however, isn’t talking about offsite adoptions. He goes further. Wouldn’t it be more ethical (meaning more cats would be saved) not to have people come to your adoption booth, but to literally stop people in the street and hand them a cat? Literally, hand each person who walks by a cat. Again, if the certain outcome in the shelter is that eight of the 10 will be killed, can’t we assume that more will be saved, in fact more will be loved for the rest of their lives, if we do that?

He is, of course, using a rhetorical device to teach his students to become critical thinkers, to challenge their knee-jerk assumptions and to weigh the evidence. If we did that, how many animals will become cherished companions? While not a perfect analogy, a national study showed that animals were least likely to be given up if they were acquired as gifts. Moreover, humans are capable of very deep and very noble impulses. Given how much Americans love their animal companions, wouldn’t it be more likely that they would save those cats than not?

How many will be abused? According to national data, we share our homes with 165 million animals. Only about six million or so of those ever enter shelters—and only four percent of those animals arrive with evidence of neglect or abuse. I am not downplaying it and any abuse is horrific. The fact is, however, the first time many companion animals experience neglect or abuse is when they enter a shelter. In other words, keeping them out of such places all together would actually lower the incidents of companion animal abuse.

And were animals to be given away in such a manner rather than placed into the places that abuse and kill them, how many of them will be released on the streets? And how many of those who are will actually find a home from there? In fact, the likelihood of being reunited with their owners is greater for cats if they are allowed to remain where they are rather than being admitted to the shelter. In one study, cats were 13 times more likely to be returned home by non-shelter means (such as returning home on their own) than by a call or visit to a shelter. And another study found that people are up to three times more likely to adopt cats as neighborhood strays versus adopting from a shelter. At the same time, the risk of death for street cats in communities has been found to extremely low, with outdoor cats living roughly the same lifespan as indoor pet cats. In other words, the risk of death is lower and the chance of adoption higher for cats on the streets than cats in the shelter. In a study of over 100,000 alley cats, less than one percent of those cats were suffering from debilitating conditions.

When I ran a shelter, we did adoption screening. The No Kill shelters I’ve worked with, both private and municipal, also do adoption screening. When the lives of animals aren’t on the line, we have a responsibility to do so. But the idea that increasing the quantity of homes decreases its quality is a fiction: a ruse promoted by HSUS and others to justify killing and paint the lifesaving alternative as darker. Quantity and quality can go hand in hand. But when a shelter refuses to comprehensively implement alternatives to killing: when they refuse to hold their lazy and incompetent staff accountable to results, when they neglect and abuse the animals in their care, when every challenge to overcome is used as an excuse to give animals the needle or to stuff them into a chamber in order to gas them to death, in short, when they refuse to adopt their way out of killing as many shelters in America have and every single one of them can, the last place we as animal lovers should want our community’s homeless animals to end up is inside the walls of those shelters.

Had shelters never existed, and it was proposed that a system of abusive death camps be opened to round up and kill millions of them, how many of us would support such a notion? How many of us would argue that the homeless animals for whom there was hope, whom we saw being fed, cared for and even adopted by our neighbors, would be better off entering a facility where they are likely to be abused, and likely to be killed? In fact, over 150 years ago, when the impounding and killing of homeless animals was a new concept, the great Henry Bergh, founder of the animal protection movement in North America, fought the existence and proliferation of such institutions, arguing that stray dogs should be left alone, once famously and without hesitation asserting, “Let us abolish the pound!”

Of course, we do not need to create death camps. We can create true shelters in the dictionary definition of the term. That is, of course, the ideal and the goal of the No Kill movement. And then we can screen homes to make the best matches between people and animals. But that is not what we have. And we cannot pretend otherwise. In 2012, what our nation’s shelters can be and what they are are worlds apart.

In Davidson County, North Carolina, the pound not only kills nine out of 10 animals, it does so in one of the most brutal ways possible, putting different species into the gas chamber to sadistically watch them fight before turning on the gas. In Memphis, Tennessee, animals are forced to cannibalize other animals to keep from starving to death. In Chesterfield County, South Carolina, cats are beaten to death with pipes and dogs are used as target practice. In Dekalb, Georgia, workers kill cats by “holding them down with a foot on the back, sometimes breaking their bones.” In Cabel-Wayne, West Virginia, animals are simply thrown into the trash alive and sent to the dump in garbage bags. As I document in the 270 pages of Friendly Fire, these are not aberrations. How can we, as animal lovers, condone animals being placed at the mercy of such institutions? How can we prefer such treatment to the compassion the evidence shows they are far more likely to get from your average, animal-loving American?

In other words, given the current obstinacy we face from shelter directors and their allies at the large national groups which fight us in our reform efforts, two questions become logically inescapable: Wouldn’t our nation’s homeless animals be better off if these shelters did not exist? And wouldn’t the animals be better off if we took them to populated areas and simply gave them away?

Our initial, emotional response, conditioned by years of misinformation about the true nature of animal shelters and the blame laid at the feet of the American public by the nation’s large animal protection groups may cause us to initially say “No,” but all the evidence says the opposite. And if it was our life on the line, so would every one of us:

For further reading:

—————-

Have a comment? Join the discussion by clicking here.

My Facebook page is facebook.com/nathanwinograd. The Facebook page of my organization is facebook.com/nokilladvocacycenter. Many people mistakenly believe that the Facebook pages at No Kill Nation and No Kill Revolution are my pages. They are not.